Elevated Rail is an Urbanism Cheat Code

Sometimes you really can ride your train and eat it too

Epistemic Status: Mostly backed up by extensive research. Sources are linked.

Broadly speaking, there’s two types of online urbanists worth reading1:

People who advocate for improvement via paradigm change: These people have some general preferred paradigm (usually either YIMBYism or deprioritizng cars in favour of other forms of transportation). They argue (generally convincingly in my opinion, although details matter), that replacing our high level paradigm like this will lead our cities to be much nicer places overall (though possibly with tradeoffs). Here’s an example of this type done well.

People who focus on technocratic improvements, pointing out how various technical areas of bad regulations or badly run government agencies are destructive and could be better run. Single-stair building reforms are a common issue for them lately, but the classic example is Alon Levy and the Transitcosts project’s extensive research into building cost-effective metro systems.

Overall, these are both important areas that I mostly support. They require a lot of in-depth detail-oriented work to unlock all sorts of real improvements that could make all our daily lives better while reducing cost of living. They don’t come easy - paradigm change requires gradual political change in an age when politics is often uninterested in everyday quality of life issues, and technocratic improvement requires gradual reforms, policy and staffing changes, and learning to get a lot of things right.

This is great and all. Eating your vegetables is important. But at some point you have to ask - where’s my candy?! Where by “candy” I mean “easily described urban improvement that lets us save huge amounts of time and money on transit projects with basically no downsides”.

But there actually is an answer to it, which is “just build elevated metros”. The efficiency gains are insane. This doesn’t get enough mention2 (though not none - Reece Martin made a video about it last year), but it’s the easiest urbanism win you can have3.

Big Wins

The single biggest thing it that it’s over twice as cheap to build. Even without adjusting for the fact that els are typically only built in high-cost countries, we get a factor of about 1.8. Adjusting for that gives a ratio of a factor of anywhere between 2 and 4.

For the same reasons, you can build els 2-5 times faster than underground lines (typical project timelines for an el line are 3-7 years, compared to 8-20+ for a fully underground line.

Tunneling is expensive, and while modern Tunnel Boring Machines help somewhat, they’re still slow and expensive. Better TBMs wouldn’t solve the cost gap though - stations cost at least as much as tunnels even in cheap systems (digging underground is hard). You also need to bring in and use heavy construction equipment, tracks, the trains themselves, electrical equipment, and so on and then use it in a narrow underground tunnel (and, of course, you have to get all the dirt out). Power transmission and avoiding running into buries utilities (if you even have a good utility map, which you often don’t), are another problem. So is geology in places where the tunnels might collapse (and you have to do a lot of geological work upfront to even know what kind of challenges you’ll be dealing with - and even then, you can run into surprises that require planning changes during construction). You risk digging too deep and awakening that which should have been let lie. The list goes on.

To put this in perspective:

The original Montreal REM extension was planned to cost about $10 billion. Citizen objections pushed them to move the project underground, pushing estimated costs up to $36 billion for a much smaller extension that wouldn’t even link to downtown, which is too expensive and made the project DOA.

The Tel Aviv Metro is planned (assuming no delays, which there almost certainly will be) cost $41 billion dollars and start operation of different sections in 2032-2040. If they switched from fully underground to elevated, they could save at least $20 billion dollars (assuming the lowest plausible multiplier and zero cost overruns - both are likely higher, which would result in higher savings), and being operations of the first phase by 20284 and the full system by 2032.

The NYC second Avenue subway, despite being just three new stations instead of a whole new system, has almost identical cost and timeline estimates. This sucks, but it also means we could get the same savings for the city of New York if we could move it aboveground5. The savings would be much larger in practice, since the giant stations account for 77% of the costs and we could save basically all of this by building aboveground (even without getting into savings on tunneling costs).

People have a bad habit of forgetting this, but money is fungible. If you’re a diehard transit advocate who wants as much transit as possible, pushing for an elevated system lets you have three times as much coverage, the difference between “some people can take the metro to work sometimes” and “almost anyone can take the metro from anywhere to anywhere”. If you have different priorities, that’s tens of billions of dollars you can put them towards, or just a massive tax refund for everyone in the city6.

And speed matters too. If you build an elevated system, you can have it faster (if you’re a mayor or governor who wants to move fast, you can bring it from planning to an actual open ridable mass transit line within a single four-year term in office - just in time to point at it as you run for reelection). Screw planting seeds for trees your grandchildren will sit under. Plant faster seeds and sit under your own damn trees.

I mostly compare els to underground lines here, but it’s also worth comparing to trams. I think trams are mostly not worth it - they give you a 2-5x cost reduction compared to els, but grade-separated rail is about three times as fast and has 5-10 times the capacity. Trams may have their role in some cases7, so I’m not entirely writing them off, but they’re mostly an inferior replacement8.

Smaller Wins

Even aside from the massive topline wins, there’s a whole bunch of nice benefits to els:

The same benefits for construction costs also apply to maintenance and operations costs: Running maintenance operations is just so much harder in narrow underground tunnels than on an aboveground platform, and has more issues with crew safety and equipment access. Energy costs are higher underground (where you need heavy HVAC and 24/7 lighting). Tunnels degrade from water/humidity issues and need to be maintained. Overall it’s roughly twice as expensive to run an underground than an el.

Doubling costs makes a major difference. The Singapore MRT’s elevated lines are net profitable (avoiding the Endless Emergency9), while their fully underground Downtown Line loses money every year despite heavy ridership.Better reliability: Easier maintenance doesn’t just mean less costs, it also means you can get maintenance done more easily and avoid delays or extended shutdowns for repairs10.

If something does go catastrophically wrong (which should ideally never happen, but can), it’s a lot easier to evacuate people on aboveground tracks, as demonstrated by the Singapore MRT last year.

Better station access: Underground stations are often giant mazes where it takes multiple stairways and tunnels to get to the platform, but elevated platforms are easy to just get to in one short hop from street level.

Paya Lebar MRT station (source). Just walk up to it and up a short staircase to get to the platform, no giant tunnels or multiple escalators needed. This is underrated in general. Time to platform is an underrated part of transit planning. Building large stations where it takes 3-5 minutes to get from the street to the platform adds about eight minutes to every trip (the equivalent of traveling four or five extra stations, or the difference between catching one at peak frequency where a train comes every two minutes, and waiting for one in the middle of the night where it only comes every 15-20).

Nicer ride: It’s generally a lot more pleasant to ride high up and see the city as you go than to be stuck in a dark tunnel underground11.

Elevated lines are also more visible from outside, which helps with legibility. It’s easier to find and reach a station when you can clearly see where it is (I’ve lived in New York for years and still sometimes have a hard time finding the entrances to stations, even in stations I’ve been before).

Tunnels tend to end up used as improvised homeless shelters, which both makes transit use unpleasant for riders and is dangerous for the homeless themselves12. It’s a lot easier to keep tracks and stations free when they’re small, simple and well-lit aboveground platforms and not underground cave complexes.

It’s a lot easier to add elevators to aboveground stations than to drill shafts for them (especially in multilevel underground stations).

You don’t have to build heavy infrastructure to enable underground phone service, you’re aboveground and it just remains available by default13.

Aside from being easy to electrify, it’s also easy to add things like Platform Screen Doors (since you’re not trapped underground where you have to expensively dig every extra millimeter of space, and you don’t so many need support pillars to hold the station up).

While I’m on the subject of side comments, it’s worth noting some systems (like Vienna or Amsterdam) have surface-level segments that run like grade-separated metros by using natural canals or fencing. This is great when you can get it (building at surface level is even cheaper than elevated in terms of construction costs), but it can require having a natural canal or right-of way you can use and can have high land use costs. It also forces you to build the line in areas with enough open land for a surface-level train track, which is anticorrelated with the dense areas you want to make accessible by transit.

Why are we not funding this?

At this person a naive person might ask, if els are so great, why aren’t we building more of them? They get a bad rap for three reasons. Two of these are basically always wrong. The third one is occasionally fair but is still usually wrong.

The biggest reason is noise. As someone who hates noise more than most people14, I get this. The kind of elevated trains we have in New York and Chicago are ridiculously loud (about a hundred decibels, as loud or louder than a busy highway full of honking trucks).

But this just isn’t true anymore. Modern elevated trains are about 60-75 decibels (about the same as a typical two-way urban street. Remember, decibels are on a log scale, so 70db vs 100db is a difference of three orders of magnitude).People think els are ugly.

In fairness, everyone is entitled to their taste and mine might be weird here, but I think els look perfectly nice and aren’t ruining any views (especially since they’re usually build in ugly-ish road medians anyway). I also think it’s worth it for the people riding the train to have nice views15.But the real issue here is the things that don’t happen. Train riders aren’t magical creatures summoned by the train out of thin air - they’re people who already exist and need to travel somewhere anyway. Building els does enable some trips to happen that otherwise wouldn’t, but most trips would still have to happen, mostly by car (and occasionally by bus, bike or taxi). Which means every train line build displaces urban highways, roads and parking lots (not to mention lots and lots of traffic congestion).

Some numeric estimates: A single heavy metro line can have a capacity of 30-60 thousand passengers per hour per direction. To support that with car infrastructure under ideal circumstances, you would need 3-5 four lane urban highways (about ten total lanes per direction) and about 220 acres (roughly a square kilometer) of parking lot16. No matter how ugly you think an elevated train line over a highway median is, it’s not uglier than twenty road lanes and a kilometer-wide parking lot.

Land use: Els require a lot more land than tunnels, especially if you’re adding them to an already built-up area. Sometimes, in especially dense or old downtown areas, there really just isn’t enough room. Especially hilly cities, like Hong Kong or Jerusalem17, can also have issues with elevation if you’re building things aboveground. Singapore is building a new MRT line underground to avoid building under the park and a built-up neighborhood, and it’s giving them construction hell.

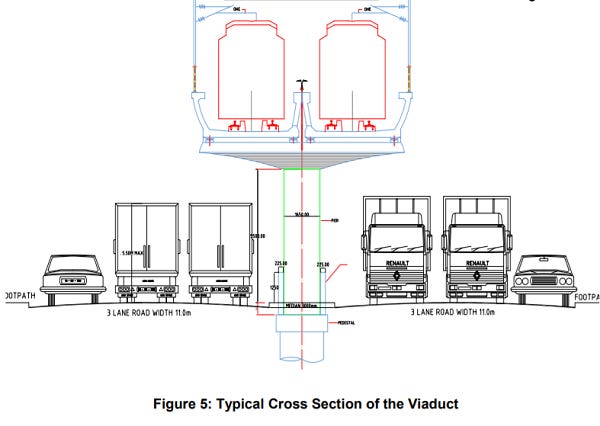

It’s pretty rare for this to be a real problem though. Most cities already have at least a few wide arterial roads you can build els over already. And you just don’t need that much space for them - the tracks themselves need some clearance (about 7-13 meters total), but the pier footprints only need about two meters. For comparison, a protected bike lane is also just two meters, a typical bus (or car) lane is three meters, and a tram is ten meters wide. If you have enough ground space for a bike lane, you have enough for an el. If you have enough for a tram, you have enough for an el plus two car lanes underneath it (or a park). If your city is busy enough to call for a metro line, it almost always has the room to build it.

I think this is going to be important going forwards. If self-driving cars really do take off, they could increase congestion to unmaintainable levels. On the other hand, they provide perfect complementary service for metro lines (being able to run last mile-and off-hour services at times congestion is less of a worry). If the whole abundance movement does take off, it’ll have both the opportunity and need to build a bunch of metro lines across America. Let’s try to do it right.

Discounting hardcore culture warriors, which generally aren’t.

The reasons why are complicated. Maybe it’s the bad rep, or that there’s just not much to say about it so people who write a lot about urbanism talk about it a bit and move on, or maybe just that most writers aren’t efficiency-minded enough to notice how huge the gains are on this.

There’s a few others on transit construction - building smaller stations and putting stops roughly a mile apart (or 400-500 meters for buses) are also relatively easy improvements, for example. But there’s nothing that comes close to just building it elevated.

Realistically it would be later, given typical Israeli building delays. But then I doubt the underground metro will start operating in 2032, so the relative time savings are still almost certainly more than four years.

The interface with the existing subway would be hard, but the actual terrain isn’t - there’s plenty of room for a viaduct in the middle of second avenue.

That said, I’m not actually advocating for this one - if we could somehow convince the MTA to care about efficiently building subway extensions we should start with ones that don’t already have contradictory planning and where it would be easier to connect it to the existing system, like extending the N to LaGuardia. This one’s just about illustrating how easy it is to find tens of billions of dollars lying around on the ground here.

For a sense of scale, the difference between the Montreal underground and elevated REM plans comes to over ten thousand dollars per resident.

Although the emerging alternatives of micromobility and self-driving cars can mostly fill the role of trams pretty well (while serving to complement rather than replace heavy metros). I expect heavy metros to become more useful as the future (as self driving cars solve last mile transportation issues but increasingly stain the capacity limitations of downtown roads), while trams become less useful (they’re mostly good at low-capacity shorter-range transportation, which is a transportation form more easily replaced by self-driving taxis or scooters).

The most extreme case of this is the Tel Aviv Red line, which operates as a high-speed automated metro system downtown but slow light rail in the suburbs. This makes it the worst of both worlds - the suburban extension cost about half as much per mile as the downtown segment but is functionally almost useless, and it makes the whole system tediously slow. They could easily have just build it elevated in the non-downtown segments and run it as a fully automated high-capacity, high-frequency metro for the whole route.

The issue where transit systems lose money per rider, meaning that the incentives are actively against improving the service because that would make them need more subsidies which may not be available.

Unreliability is awful. public transit should always, always deliver what it promises to. It needs to be reliable.

Shoutout to the airport tourism help desk guy in Hong Kong who recommended taking the bus into town so I could see the city. He also sometimes takes the (slower, more expensive) bus just for the views.

A dark secret about the NYC subway system is that is occasionally runs over homeless people hiding in the tunnels.

Okay, this one is arguably a minus. Some people prefer to have a forced break from their phones, and it helps deter people from having loud phone calls on the train.

Another low-hanging fruit to improve everyone’s life would be to make car horns cost a dollar per use. As for trains, the FRA badly needs to repeal their regulations mandating frequent loud use of horns for trains using public crossings.

Trains generally have more people inide looking out than people outside looking in. Most people don’t stare at train lines that much.

This assumes free flow traffic and no congestion; in practice the car load also has a lot of congestion to the side streets that need to absorb the cars coming on and off the arterials.

I say “Hong Kong or Jerusalem”, but really Jerusalem is almost unique in both being hilly and having populated neighborhoods on hilltops surrounded by valleys. Most famously hilly cities, including Hong Kong and San Francisco, have most people living in the flat part of the city and could easily build most of their lines aboveground (the San Francisco BART lines pass under market street, which is so flat they could just as easily have gone above it). Even Chongqing, which is famous for its insane elevation changes, has a bunch of elevated metro lines.

My only critique with regard to the Tel Aviv metro is that it is probably worth the additional expense to put it underground. A rocket hitting a viaduct and taking it off line would be very burdensome to fix. The entire metro also serves as a dual use bomb shelter. I think the Moscow metro can even withstand nuclear blasts. I think Yitchak Navon would probably be able to survive a nuclear strike as well.

Edit: I am writing a book on Israel and a big part of it is on urbanism. What I have diagnosed as the main urban planning problem is that for whatever reason Israelis think the Corbussier apartment building in the middle of nowhere surrounded by parking is a good idea. It is quite literally the worst style of urbanism. American subrbanism would be a ginormous improvement. Going on Google street view and looking at Kiryat Gat gave me a headache. Townhouses townhouses townhouse and more townhouses! I am also generally against high-rise residential buildings as they have very negative effects on birth rates. It is probably worthwhile to mandate a law that all apartments have at minimum 5 bedrooms/6 rooms.