Epistemic status: Sometimes I say things. Actual Hong Kongers feel free to correct me, but I’m especially interested in comments about the things I didn’t even notice I missed.

I always put in a disclaimer at the top of these about how I can only have a limited understanding of places I’ve only visited1 and so on. But this time I want to double underline this. Because despite having spent a lot longer in Hong Kong than anywhere else I’ve reviewed (including spending a lot more time talking to locals), this city remains the most alien and incomprehensible place I have ever been in2. I’ll do my best here, but seriously. This place is weird.

My sense is that there’s three underlying cultures involved. There’s the western outpost subculture, which has evolved to be your standard global city culture, just like New York or London. There’s the native Hong Konger (cantonese?) culture, which is a bit of an odd duck3, since it’s inherently composed of immigrants (Hong Kong was never a major city in pre-british times). And there’s the mainland influence, which comes in two distinct flavours - top-down CCP influence (this has famously been a point of contention and mass protests since 2019; you see it mostly in top-down propaganda), and ordinary people moving from the mainland (which fall mostly into the second group)4.

The second group I would describe as incoherent pre-CCP chinese culture. It’s by far the largest and most influential, and it’s also the most incomprehensible - partly because it’s chinese5, but also because it’s such a mishmash of immigration waves that it doesn’t even have a coherent self-organized culture in itself6.

Before coming to Hong Kong, I thought it would be more like Singapore, with the shared history of being a majority-chinese British trading post in East Asia.

It is not remotely like Singapore. Partly it’s just having less British influence (Singapore was the main British trading hub in East Asia, while Hong Kong was more of an afterthought. To put some numbers on it, the British had only 14,000 troops defending Hong Kong from the Japanese but 85,000 in Singapore). Mostly though, it’s the illegibility.

Illegibility

Illegibility is hard to describe, but fortunately Hong Kong gives many examples. The first one starts before you even get there - trying to figure out whether you need a visa (or how long you can stay without one) is a confusing mess of navigation7. Actually getting in is easy, you just show your passport to someone who waves you through8. The flip side of illegibility is that Hong Kong seems extremely low-crime and organically high-trust9. When I actually got off the plane, the tourist information stand guy was just a random retired guy who was extremely enthusiastic about the city, who helpfully recommended taking the bus so I could see the views on the ride in.

This sort of thing show up everywhere. A majority of food places don’t take credit cards, but there’s no single payment method you can use everywhere. Most places will take some random subset of cash, Octopus card, credit card, Alipay, Wechat pay, Google/Samsung pay, but which one they take is wildly unpredictable. You do learn some heuristics; more upscale places and places on the island are more likely to take credit card (and occasionally don’t take cash), while Kowloon side places are more likely to take ali/wechat pay (being more chinese). Most places will take Octopus cards, but I can’t figure out if it’s even possible to fill up an Octopus card any way except with cash10.

Grocery stores are also a bit of a mess - there’s some good grocery stores with everything you need, if you’re familiar with the city and know where to find them, but most of the stores you run into just walking around are small convenience stores with only a few random things (e.g. they’ll have vegetables but no meat, or drinks but no fruit. I had a pretty hard time tracking down laundry detergent). Most of the places you run into that do have meat are wet markets11, the perfect example of illegible commerce (I wouldn’t even know where to start shopping in one of those; you definitely can’t use credit cards and the sellers seem to only speak Chinese12).

The biggest thing though is the city itself. It’s a lot more pedestrian friendly than Singapore (or, afaict, cities on the mainland), not because it’s planned that way, but because it’s chaotic. Which brings us to the next section:

The spirit of Kowloon Walled City

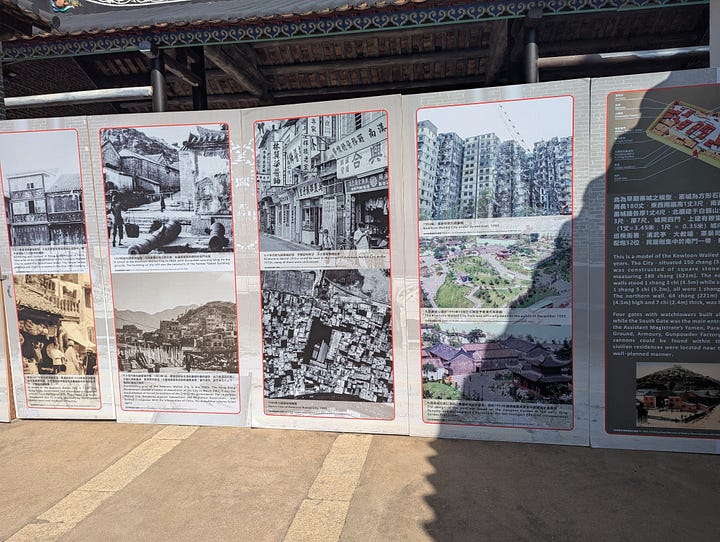

In 1810, the Qing dynasty built a small fortress in northern Kowloon to prevent British encroachment after the First Opium War. When the British leased the northern part of the Kowloon peninsula in 1898, the Qing government never officially ceded the Walled City itself, which led to it being a legal grey area. The British government didn’t bother to fix it13, and the Qing dynasty itself collapsed shortly afterwards. Between the warlord, the chinese civil war, the japanese invasion, the chinese civil war again, and the CCP being busy with other stuff, there was no chinese government bothering to actually claim the area for a while. There were, however, quite a large number of refugees from the various wars and famines happening on the mainland who needed somewhere to run where there were no authorities to kick them out or stop them from building housing. And so was born Kowloon Walled City to haunt the dreams of a thousand generations of YIMBYs.

KWC is gone now. The Hong Kong authorities finally tore it down 1987, and all that’s left where it once stood is a small museum and a very nice park. It had evolved into an ungoverned maze of illegal construction, industry, and crime, with thirty thousand people living in an area of 0.01 square miles, making it the most densely populated area in human history, and the local authorities got permission from the CCP to tear down their unsightly slum. Where tens of thousands of people once lived, you can now walk almost alone.

But still, the spirit of KWC is everywhere. Hong Kong is famous for having more skyscrapers than any other city, but that’s not because they build lots of fancy modern towers like New York or Shanghai. It’s mostly just that high rises are the default form of construction, like rowhouses in Amsterdam or public housing blocks in Vienna. They don’t seem to mind just casually building tall buildings everywhere. In the newer areas this results in new, more planned out neighborhoods where a single builder just organizes and builds the whole area.

But most of the city isn’t new and mass produced. Most of it is just produced on a “heck let’s just build stuff” mentality which is a textbook organic unplanned city. It’s exactly described in Seeing like a State:

Natural organically-evolved cities tend to be densely-packed mixtures of dark alleys, tiny shops, and overcrowded streets. Modern scientific rationalists came up with a better idea: an evenly-spaced rectangular grid of identical giant Brutalist apartment buildings separated by wide boulevards, with everything separated into carefully-zoned districts.

Hong Kong doubles down on this by not only having dark alleys, tiny shops, and overcrowded streets outdoors, but having them in indoor spaces. My first time arriving in town, I stayed at a hostel downtown. In order to find it you had to walk into the ground floor of a sleazy mall and find some tiny elevators14. These led to a large abandoned-looking lobby area on the fifteenth floor, with an internal shaft full of air conditioners and an office in the corner. The hostel itself was spread over corner rooms in four different floors of the building, with the majority of the actual space in those floors just being dead. Everything in Hong Kong is like this15.

One consequence that I haven’t seen anywhere else is old worn-down high rises. In New York or Tel Aviv, you’ll get high rises, which are mostly fancy expensive new construction, and older lower-rent housing, which are slightly dilapidated 3-6 story buildings with windows featuring external AC units or clothes hung out to dry. In Hong Kong you get the same class division, except the dilapidated low-rent buildings are also thirty or forty floors high, which feels incredibly weird, like meeting a rabbit the height of a giraffe.

There’s also businesses on the third or fourth floors of buildings (or, which is worse, something that’s the ground floor on one side and the third floor from the other side, if the building is on the mountainside). If you’re lucky, there’s a sign on the ground floor telling you how to get in, hopefully with a staircase right to your building. If you’re unlucky, you have to figure out that you need to go around the side, through a residential building-looking lobby then take a tiny elevator up to the second floor16 , then turn left to follow the sign for a hairdresser shop and you’ll see the cafe you were looking for on the way. Also remember to go out the way you came and not through the staircase that seems like a better way if you’d only noticed it first, in case opening the door to exit the building through it triggers the fire alarm.

There’s also skyways. I saw a few of these in Singapore (mostly to go over highways), But in Hong Kong there’s a massive interconnected network that seems to cover half the city. But not fully connected enough that you can just go anywhere to anywhere on them, because that would be too easy. Instead you have to figure out when you should get on or off and when the skyway looks like it’s going a couple more blocks in your direction but there’s no actual exit that way so you’d better get off now. Google Maps does not understand the concept of skyways and cannot help you. Good Luck and have fun.

There’s also a ridiculous amount of outdoors public escalators, which makes sense given how much vertical climbing people have to do on the mountainside. Apparently they change the direction throughout the day based on people’s commute direction, which is a nice touch.

I feel obligated to mention here that Hong Kong seems like a truly terrible place for anyone in a wheelchair (they have elevators, but not everywhere, so having at least some minimal ability to handle stairs is important).

The other category of person who would absolutely hate Hong Kong is Scott Alexander, who should definitely never, ever go there. It doesn’t have anywhere non-crowded or non-skyscraper-y, to a point that sometimes wore even on me (and I usually love skyscrapers). To people who dislike them, this place would be hell.

You might have gotten an image of what Hong Kong is like in this section, and have decided, based on that, to teleport into a random point in Hong Kong. At which point you would be pretty surprised, because…

Hong Kong is wilderness

Most of Hong Kong looks nothing like what I said earlier. Mostly of Hong Kong, by area, looks like this

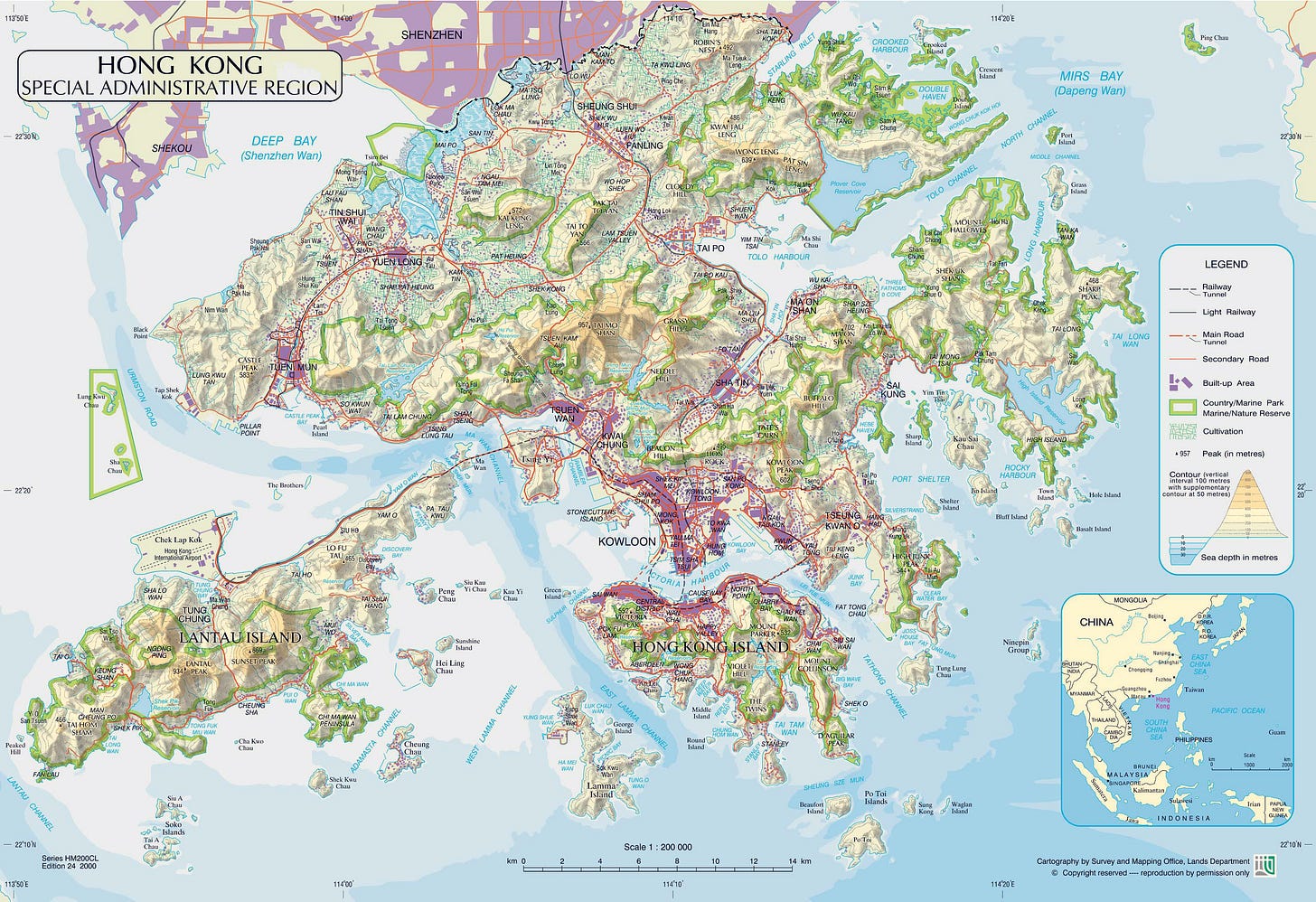

Seriously, here’s a map of the built up areas of Hong Kong

Outside of a couple of dense strips on the north side of Hong Kong Island and across the bay in Kowloon, most of the city is empty mountains. You get some more cultivated areas and a few more dense clumps in the New Territories, but mostly there’s just… nothing. Empty mountains and nothing else.

So despite having a population almost as large as New York, Hong Kong feels surprisingly small. There’s a few high-density areas, but they can feel almost like a small band of campers on the edge of untamable wilderness.

I’m not sure why it’s so lopsided, this isn’t a form of urban planning I’ve ever seen anywhere else17. There’s the obvious geographic constraints (it’s hard to build on mountains), and the secondary ones (if you did build on mountains - or even just on more of the flat areas - you’d have to do transportation for them, and since Hong Kong is mostly too dense to be drivable that means a lot of trains and buses). But it does seem like there has to be a pretty weird cultural and legal structure for construction to be this focused on residential high rises in a few dense areas (part of that would be making it easier to build high rises, but I wonder how much of it is making it hard to build midrises or houses in wilderness areas).

There is some historical basis - the British historically had more legal and practical control over the island and lower Kowloon than the rest of the region for much of its history - but the British never had an issue figuring out how to expand control over rural villages elsewhere in their empire. And the city is somewhat concentrated around the port, but that’s true of other port cities too, and they don’t look like this.

It’s probably some conflation of all these factors, but it’s another thing on the list of rhythms I don’t quite get about Hong Kong. I do recommend doing some hikes if you visit though.

The MTR

The Hong Kong MTR is, by the numbers, the best metro system in the world. Hong Kong has 80% transit mode share (and only about 10% car mode share), making it by far the most transit-oriented city anywhere in the world. It’s not only unsubsidized, it makes billions of dollars in annual net profit despite costing less than half as much per ride as the NYC subway18. It’s incredibly heavily used all the time, with trains that are even longer and wider than NYC subway trains running every 2-3 minutes most of the day being crowded (pretty much the only time I managed to get a seat was when I got on at the end of the line).

It also does a great job handling the chaos that is the rest of Hong Kong. Hong Kong businesses use six different payment methods? The MTR has gates that accept all six at every station. Stores and boundaries are confusing elsewhere? Every MTR station has the same three food places selling the exact same snacks open the exact same hours, with a clear divide between the public and paid station areas and a brightline rule saying you can only eat in the former. The streets may be a maze, but every MTR station has clearly labeled exits with internal directions to every exit (which means if you’re coordinating to meet someone in a neighborhood one of you isn’t familiar with, the best way to set it up is to arrange to meet at a specific MTR station exit).

I’m going to wonder out loud if some parts could have been better designed here, but I wanted to start off with that. The system is really good, and while I can ask questions about why they do some things the way they do there’s a good chance there’s really good answers for all of these.

The first thing to notice is that the trains tend to be really crowded all the time. The trains are even longer and wider than NYC subway trains19 and some lines run about every two minutes most of the day while still being pretty packed (pretty much the only time I managed to get a seat was when I got on at the end of the line)20. This is, objectively, fantastic, but given the crowding I start wondering if they could increase capacity (Fully automated lines on the Paris Metro go all the way up to 42 Trains Per Hour). This may not be possible for the MTR (since the trains are bigger they might require longer pauses for loading and unloading, which is a bottleneck), but it’s also true they’re not really fully automated yet and some don’t even have modern signalling systems, so a tech upgrade might be able to increase TPH and reduce crowding. One advantage they do have over New York is not running past midnight, which gives them a (small, difficult) daily window to do maintenance and improvement in21.

The other issue is that stations are huge, with platforms multiple levels underground and station exits spanning entire neighborhoods. I assume this is the main reason why, despite being such a good system in other respects, MTR construction costs per kilometer are often high even by anglosphere costs, almost reaching the cost levels of New York itself at times22. Costs aside (as mentioned earlier, the MTR does perfectly fine financially), this does make for a lot of walking through some very crowded corridors just to reach the platforms.

I can tell a story where this is necessary. With all the high rises everywhere, there’s probably a lot of deep foundations the trains need to pass beneath, and trains that go under the harbor also have to go pretty deep. The mountains everywhere also mean that even lines dug relatively shallowly in one place might be surprisingly deep in others. I’m usually of the opinion that it’s better to just build metro lines elevated everywhere, but downtown Hong Kong is probably the one place in the world you really can’t do that. And they do go elevated in a few places outside downtown, like Sha Tin.

And for the station size - maybe making them so big and with so many entrances helps channel the crowd into manageable pieces when going in and out? you can picture humanity as a flash flood, starting with a few drops of rain at each entrance to the station and coming together gradually enough that it’s only a full mob at the platform itself, when they’re ready to board the trains.

But I can also imagine a world where it isn’t. Where the idea of building smaller and shallower stations just never comes up because they’re too used to building them deep, or some local politician who doesn’t ride the MTR himself would complain, or some project leader just really wants to build a huge station like the last guy got to. Where you could easily build a line elevated but people complain about the effect of the noise or the views on property values, ignoring the area already having a dozen elevated highways that are noisier and uglier than any train line because the people doing the complaining are members of the minority driving elite23. This sort of thing happens a lot in other systems around the world.

MTR management seem pretty competent all around, so I’m guessing it mostly is the first story. Still, everywhere has political pressures and there’s probably one or two places it’s the second.

Shenzhen and Macau

I spent one day each in Shenzhen and Macau, so prepare for some hilariously poorly-informed opinions on each of them.

Shenzhen

After a week or two in Hong Kong, Shenzhen feels amazingly calm and peaceful. They have tall buildings, sure, but there’s just so much green space and no crowds. You can just sit in a quiet cafe having breakfast in a way that’s hard to find in Hong Kong.

None of what I said about Hong Kong being messy and illegible and a bit dirty applies on the mainland. It’s incredibly organized, clean and well maintained. Everything is legible - it’s confusing and alienating if you’re just there for a day (because you have to get used to systems none of the rest of the world uses, like Wechat Pay), but once you are used to it everything is legible and consistent.

I’m going to give the CCP credit for this one - imposing unity on a place the size of China is incredibly hard and requires a level of legibility imposition not seen since Napoleon24. In order to make Shenzhen legible to Beijing, they also had to make it legible to me (well, aside from the language barrier).

If it weren’t for the language barrier and the immigration barrier and worrying about whether politics might get worse, I can see myself really wanting to live in Shenzhen. It satisfies my skyscraper and big city desires while still having some really pleasant quiet areas. I should check out Shanghai someday.

The biggest risk of Chinese style one party rule is that they can double down too hard on a bad idea, like killing the sparrows or the one child policy. But the upside of that is that they can pivot a lot more easily. Walking around the parks I learned that they used to plan neighborhoods to be more purely residential but started making them more mixed-use and pedestrian friendly when they realized the old style had problems. Meanwhile in America we realized that a while ago, but our weird legal and political system doesn’t allow us to actually pivot on this knowledge.

People bike in Shenzhen. They never bike in Hong Kong. Probably mostly because of the mountains, but also just as a cultural thing it’s not an idea anyone has.

Nobody ever feels truly secure. I talked to a local who told me how the mayor met a japanese company that was using robots made in Shenzhen, and how he’d been shocked that Japan, the former masters of robotics, could actually be importing robots for Shenzhen. To an outsider it may feel like Shenzhen is the undisputed global master of electronics, but apparently they can still be surprised by this themselves.

The people I actually met in Shenzhen were incredibly nice and friendly. Small sample size, but still.

Chinese Trains

Everything you’ve heard about Chinese HSR stations being built like airports, way too large and elaborate and with overly long lines and no power outlets in sight, is true. You also have to reserve a specific seat on a specific train in advance (and fill out the name of the train on a form for passport control).

They do have a reserved seating area for military people, although I’m not sure what the difference is. Maybe they get to have outlets.

The trains themselves are pretty great.

Shenzhen Metro may have the same issue with too-big stations placed next to large roads, but in their defence they’re not averse to building elevated rail. At one point I saw another pair of tracks being built on the same viaduct I was traveling on, so presumably they overbuilt it to start and are now working on four tracking it. This is great.

Chinese metros have metal detectors similar to Israeli train stations. I’m not sure why, China doesn’t have a large scale terrorism problem.

Chinese passport control is a pain, almost as bad as US passport control (though thankfully with shorter lines).

If you don’t have a regular card, the way to get on a chinese metro train is to tell a vending machine on the entrance where you’re going, at which point it’ll give you a plastic disc. You swipe it at that station to get through the entrance gate, then drop it in the slot at the exit station gate to get through there. This is awesome, it’s exactly how an Asimov story would imagine 21st century transit.

In general, China seems a lot more on the ball than anywhere else in terms of looking like Asimov’s vision of the future. He’d probably have preferred Hong Kong though, Shenzhen has too many open spaces for an agoraphobe.

Macau

I put Macau below Chinese trains, because I didn’t much care for Macau. Half of it just felt like a hybrid between a mediocre european city and a worse version of Hong Kong, and the other half is just a Vegas clone. And I don’t even like the original Vegas.

Still, some comments

There’s no Metro system in Macau. There is a “light rail” system that’s fully automated and elevated and has giant stations, and is basically just distinct from heavy rail in that it runs shorter trains at longer intervals. I don’t think the Chinese really get the concept of light rail.

The Cotai strip is reclaimed land between Taipa and Coloane Islands. Reclaimed land is always a cool concept, but using it to build a Vegas clone just feels like a waste. Build your own thing! Look at what Singapore did with Marina Bay Sands.

The crummy old portuguese side is on the peninsula. It has a bunch of historical portuguese stuff which is probably nice for historians, and it has dense urban areas which is probably cool to live in, but… it just ends up feeling empty. Maybe because it’s so small. I think of dense old villages as being interesting because they’re connected to real history and a larger land, but Macau is cut off from the mainland and mostly just full of tourists. It just feels too small to have a culture of its own, which feels like something you need a critical mass for.

It is impossible to stay awake on the ferry trip over (or back). Something about the combination of the soft chair and being rocked by the waves. Presumably the pilots have a special disposition to use some kind of meth-based drug to keep them awake through the trip.

Anyway, back to Hong Kong, and the specific things we still have to go through.

Hong Kong is basically New York

I started this article off talking about how alien and incomprehensible it is. But it’s also weirdly similar to New York. The government may be more functional and less corrupt, but it’s still mostly invisible, which means that like New York, the energy that actually moves the city is the unstoppable flood of people with their own dreams and ambitions pushing it up and doing things. I met people who organize hikes, swing dances, cat cafes, comedy night shows… There is a thing over the last few years where a lot of ambitious mobile people have been leaving Hong Kong for elsewhere in the world. So it probably used to have more energy than it does now. But Hong Kong past its peak still has far more bottom-up energy than most cities have in their prime. The spirit of KWC lives on.

It’s also just weirdly geographically analogous to New York. Central is lower Manhattan (there’s even a specific mall there that feels like a Brookfield Place clone). TST is Times Square25 with the surrounding business district being midtown. The empty bay between them is Chelsea. Repulse Bay is those fancy rich Long Island towns you can’t really get to by train. the New Territories are staten Island. Quarry Bay is LIC, a former poorer industrial neighborhood east of downtown that has a recent burst of modern skyscrapers and offices. Kennedy town may be DUMBO. Shenzhen is… New Jersey?

Okay, this is where the analogy kind of breaks down. New York is roughly the size of Hong Kong, but Hong Kong isn’t particularly large for a chinese city. America just doesn’t have anything on the scale of Shenzhen anywhere. We should maybe get on that.

Cat Cafes

Hong Kong has a lot of cat cafes, enough that if you google it you get “ten best cat cafe” lists which are nowhere near comprehensive. I only actually visited two of them before moving to an airbnb where I was catsitting a ragdoll and getting sidetracked.

I guess it makes sense that Hong Kong would have them. It’s dense enough to have an audience for them and full of people who’d want a cat but can’t fit one in their small Hong Kong apartments. It’s also low-fertility enough that a lot of people probably want the companionship.

The cat cafe section, for obvious reasons, has more pictures than words.

The Hong Kong history museum and the nature of chinese propaganda

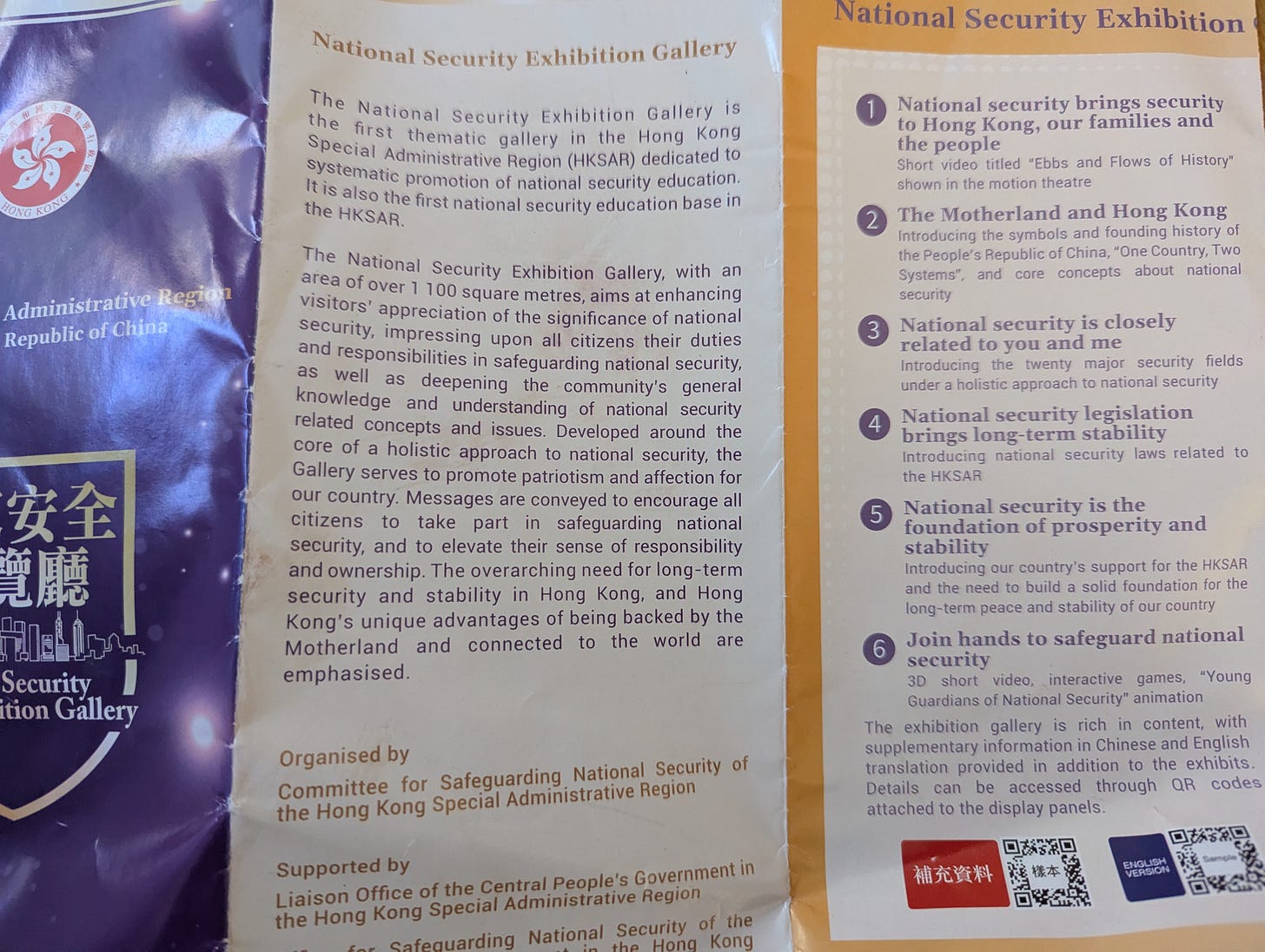

I did go to the history museum one day. This was a terrifying lesson on the nature of chinese propaganda.

You don’t see a lot of bottom-up propaganda. Bookshops don’t put “The Antiracist Baby” (or whatever the chinese equivalent is) on display, they just have books like “first 1000 STEM words”. People - whether natives or mainlanders - don’t go out of their way to talk about things that imply nationalist politics in casual conversation (or not that I caught. It is possible some stuff went over my head). It’s surprisingly restful and real-life oriented.

But the flip side of that is that the legible, top-down propaganda is very heavyhanded. The museum was full of children on school trips being taught about the importance of national security and Chinese Greatness. There’s displays about how China was victimized in the past, about how Taiwan and the South China Sea disputed areas are rightfully China’s based on archeological records and ancient history, about how China’s new military tech is amazing and surpasses the competition.

This is genuinely scary. It’s the language of a government that’s just not worried about seeming overly aggressive and starting an armed conflict, or is just brash and reckless about it. Americans are so used to thinking war is obviously bad they’re mostly not taking the possibility seriously (even the people who talk a lot about competition with China). But some kind of war (with or without America involved, maybe in Taiwan or somewhere else in the region) is a pretty real possibility people need to take more seriously.

On the other hand apparently Trump conceded the new cold war to China last week. Which honestly may be for the best. I don’t think America as it is would come out of that conflict well. Maybe avvepting that is a good first step to realizing we need to be less of a vetocracy and be able to do more stuff again. Or maybe it’s the first step in a long decline, like the British Empire after the world wars. I guess we’ll see over time.

Misc Waterfront Features

Hong Kong effectively having a two-sided waterfront (one from the island and one from the peninsula) is pretty neat. New York has something similar with the East River, but the Hong Kong version probably works better.

I mentioned earlier that Hong Kong seem to see skyscrapers in pretty utilitarian terms. There’s a lot of tall buildings but surprisingly few vanity skyscrapers, especially supertall ones. This is partly about the utilitarian attitude and also apparently partly about airspace issues (especially for the old Kai Tak airport, which was on the peninsula and right next to downtown. Most of the supertall buildings in the city were built after the airport was moved out to Lantau Island in 199826. There are two exceptions, one on either side of the bay.

I had a debate with a local over which one is Orthanc and which one is Minas Morgul. We settled that the IFC Tower on the island (right) is Orthanc since Isengard is effectively an island and has a more internationalist tech-focused culture, while the ICC tower (left) is Minas Morgul (the tower on the other side of the mountains from the major empire, an outpost on a peninsula that’s semi-independent but still loyal to the mainland).

There’s also this display on the edge of the water of street lamps through history.

Final Thoughts

Hong Kong isn’t an easy place to be. The illegibility thing is genuinely tough. And then there’s the thing is that it’s never not on - unless you go out to the mountains, there’s nowhere you can really be away from skyscrapers and crowds in. I like doing the thing of just going to get coffee and read somewhere relaxing, and while I found a few nice places there’s nowhere really relaxing in the city.

It also feels fragile, in some ways. When they moved the airport they had to shut down one and open another on the same day with zero room for error. It’s impressive as heck that they pulled it off, but it’s scary that they had to. The MTR has a similar dynamic - it’s so much better than the NYC subway in most ways, especially reliability, but it also has to be reliable, because there’s a lot less line redundancy. Buildings don’t often collapse in real life, but it’s easy to imagine one high rise falling over and tipping over every building on the island like a giant pile of dominos27.

But still, of all the places I’ve been, it may be the best. I said once that if I moved to Germany, I’d probably live in Berlin and then talk about how I wished it was more like Munich. Hong Kong is the extreme of this: I may talk about dreams of moving to a small town in Switzerland, but I have actual plans for living in Hong Kong, at least for a while. Hong Kong has some downsides but lots of upsides, and I’d rather be somewhere that has both than somewhere with neither.

Heck, I only have a limited understanding of places I’ve lived in for decades.

What does it mean to understand a city? I think of this like The Name of the Wind - there’s something like an everchanging complicated tune that you can sort of intuitively grasp that gives you some idea of the underlying structure of the place. I sort of get it for, say, Dallas or Prague or Singapore. I don’t have much of a sense of it for Hong Kong.

As an aside, it’s surprisingly hard to find ducks in Hong Kong restaurants (even the ones with ducklike things usually just have goose). I guess this is one of those differences between western Chinese food and actual local food there.

There’s a geographic cultural divide too, with the island side being a lot more international and english-speaking while the peninsula is much more heavily chinese.

And since it’s been relatively sheltered from direct CCP modernization efforts, it may be the most authentically old-chinese culture anywhere now, except maybe Taiwan.

In a weird way, the most similar place in the world to this is probably Tel Aviv - you have international influence but also a century or two of multiple immigration waves from all over europe and the middle east, with some elements of shared jewish culture but no single unifying essence. I wonder if Tel Aviv would be as incomprehensible for visitors as Hong Kong was to me - I suspect it might be, given how incomprehensible it is to me despite having lived there for years and grown up in Israel.

Compare Singapore, which has a straightforward online application telling you exactly how long you can say and which form you need to fill out. Also noteworthy that it’s more legible in the James Scott sense, as it requires filing in when you’re leaving and where you’re staying. Mainland China is similar.

This is, confusingly, not done by a machine, at least for non locals.

Which is odd for such an immigrant-heavy society. Possibly the high rents help.

The internet claims you can fill it with a credit card. People I actually met there claimed you couldn’t, and I couldn’t figure out any way to do it. Presumably it is somehow possible, but, well, you see my point about illegibility.

As an aside, seeing just how many wet markets there are does update me slightly back towards the lab leak theory of covid, since the prior on a random pandemic outbreak just happening to start in a wet market look a lot higher once you realize how common they are.

I’m not sure whether that’s Mandarin or Cantonese. There’s definitely some kind of tension between the Cantonese and Mandarin cultures in the city - one white guy who does speak Mandarin told me that while on the mainland they’ll go along with it, in Hong Kong they’ll usually try to shift into English because they’re protective of the local culture. But then the mainlanders I spoke to (who speak Mandarin) told me people will just answer them in Mandarin. Add it to the “Hong Kong is confusing” list.

Another example of a Hong Kong government just not caring to impose legibility and governability on a small but meaningful part of its land.

There were two elevators in the bank, one of which only went to even floors and one of which only did odd floors. It’s a nice trick I saw in a few buildings to handle the classic problem of “We have to mange people flow for a thirty story building with just a pair of tiny elevators”.

Not literally everything. But a surprising amount of it is, and no area seems really exempt.

second floor means third floor, and ground floor means first floor, because british.

On parts of the island there’s just three or four rows of buildings between the bay and the mountains, kind of like a real life version of NEOM except with better reasons and views.

For comparison Swiss Rail, which is also an amazing mostly-unsubsidized system, has some pretty expensive tickets. I don’t blame Swiss Rail here, they have a tougher problem in having to cover a larger and more sparsely populated area, but still.

Not to mention having open gangways and longitudinal seating, which increases capacity even more.

Interestingly the Dubai metro was also about this packed. I’m not going to talk about my trip to Dubai here - it wasn’t particularly interesting - and their metro operations are definitely much worse than the MTR’s. But still, their metro sees surprisingly heavy use, which is worth noting for a city that’s really not known for even having public transit.

On the other hand unlike New York, it would be much more difficult to take a line out of commision for a week or two for upgrades, since there’s fewer network redundancies or alternatives and ridership is so high.

The Alon Levy posts I’ve read about Hong Kong lump it with Singapore in “greater anglosphere is expensive”. I don’t know if those posts are making the same mistake I used to in assuming Hong Kong is similar to Singapore without knowing more of the culture or if Alon specifically researched Hong Kong to come to these conclusions. The cost numbers really are similar, whatever the reason.

It’s worth noting here that Hong Kong does have a clear driving elite. Maybe only 10% of the people drive, but there’s just as much space given to cars as any other city (probably more, with all the elevated highways), with most of the vehicles on the roads being fancy cars rather than buses or trucks. Maybe only 10% of people drive, but they’re the richest and most well-connected 10%, just like in New York.

Realizing this has, for the first time, given me something to actually respect in Mao. His purges and insane policies may have killed tens of millions of people, but actually bringing order and unity to a place the size of China is an insane achievement that neither the Qing nor the KMT ever really managed. And it did enable his successors to pull it out of starvation and poverty while maintaining order. It might have happened anyway, and without all those millions of deaths, without Mao (like it was in Taiwan and Singapore). But then again it might not have happened either. It didn’t with Mao’s predecessors.

I’m not sure what the second T stands for. I’d say “Terrible”, but if we started adding T for terrible to places like that than Times Square should have one too.

An interesting note on this is that they had to shut down the old airport and open the new one on the same day. They couldn’t have an overlap in operations because they were too close and would’ve interfered with each other’s airspace.

I’m pretty sure buildings don’t actually work like that.

Great post! I think Hong Kong is dense in part because of geography, but mostly because of tax policy. The government has very low income and business tax, almost all of their revenue comes from land sale, so they intentionally limit supply by only very slowly allowing more of the land to be developed. Similarly, most of the HKS revenue comes from land development rather than subway fair:

https://www.mtr.com.hk/archive/corporate/en/press_release/PR-25-013-E.pdf

Semi-Actual Hong Konger here. Just gonna dump my observations.

Duck is from Beijing

"I’m not sure whether that’s Mandarin or Cantonese." It's definitely Cantonese at a local wet market. Mandarin is mostly for tourists, or students I guess. Hong Kong is >90% Cantonese.

Urban planning: The land is all government owned, and is a pretty decent chunk of revenue. As you might think, it's a cartel bought by big business.

"They never bike in Hong Kong". People bike quite a lot, it's a recreational activity in Hong Kong, you won't see them on streets.