Lawyers are bad actually

If the rule you followed brought you to this, of what use was the rule?

Epistemic status: I am not a lawyer, but I think this is the sort of criticism where that’s mostly more of a help than a hindrance.

A few weeks ago, Some Guy wrote a post about the best justice available, arguing our justice system, for all its flaws, is run by sincere well-meaning people and mostly ends up with pretty good results. I see his point. It could certainly be a lot worse (and, in other times and places, often is). And the people involved usually really do mean well and work hard.

But still, the results are bad. Consider the following examples:

Donald Trump has been under various civil and criminal legal proceedings for the last four years (and doesn’t seem any closer co completing them). Including the case for election interference, which seems pretty relevant to have settled before he could run again. This case needed to be settled one way or another long before the election (heck, before the primary, so that primary voters could know the outcome) to have any meaning, and going into another election without it resolved hurts both his supporters and opposers.12

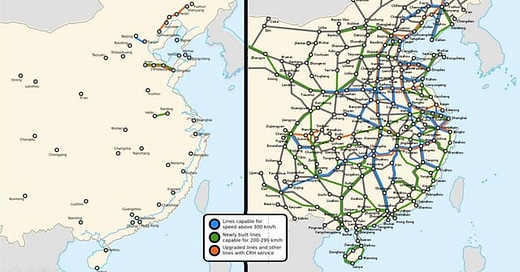

Infrastructure has become nearly impossible to build, in large parts because of endless legal review. See for example the California HSR’s environmental review timeline - the paperwork alone (without any physical construction whatsoever) is scheduled to take twenty years, from 2005 to 2025, just for phase one (they don’t even have a schedule for phase 2 approvals yet). For comparison, here’s how much HSR China actually, physically built over just 12 years3

A man named Marcellus Williams was recently executed for murdering a woman in 1998, 26 years ago. Meanwhile Khalid Shaikh Mohammed, who planned the 9/11 terror attacks, recently reached a plea deal to avoid execution. You probably feel at least one of these decisions were wrong, depending on your general feelings about the death penalty in general. But from a functional system perspective, it seems fundamentally broken for the justice system to take as long to resolve a single case as it took to eradicate smallpox and put a man on the moon combined.

A few years ago, a friend of mine had her bike stolen. She found the person selling it on craigslist, walked along to his yard and saw her bike standing there. But when she went to the police they said they couldn’t just go into his yard and seize it or arrest him without a warrant, which is a hassle to get (and would take longer to get than it would for the thief to sell the bike). So even though it was obvious to everyone involved what crime had been done by who and what should be done to make it right, the legal system had no path to allow that to happen.

The article that finally pushed me to write this was this post by Some Guy, where he argues what we have is the best justice available. Despite the many flaws in the system, he says, the trial was professional and reasonable, and the jurors all took their roles seriously, carefully considered the facts of the case, and reached a reasonable conclusion.

On the other hand, here’s his concluding description for the defendant’s (a middle aged blue-collar man)’s response to the end of the trial:

The guy cried, although not a lot. This had been going on for two years and my guess is he probably spent twenty or thirty thousand dollars on attorney’s fees. The process had already punished him well beyond the infraction.

So we had a two year trial costing the defendent tens of thousands of dollars (and presumably totally costing the system a whole lot more), over an alleged theft of a about a thousand dollars. It’s true that you need some process for punishing small infractions, but if you take a step back and just look at what happened, this is kind of a terrible outcome. It’s a rare case where calling something kafkaesque is simply accurate.

Some of this increase in legal complexity is inevitable and even good: As society becomes larger and more complicated there are more problems to handle. As technology improves and it becomes easier to do things, we need to spend more of our resources on our decision process for how to do things. As we become richer and better off, we face more downside risk and less potential upside over every decision to do something, so it makes sense to be more careful about doing things in general.

On the other hand, as all these examples show, we’re clearly handling this pretty badly.

How did things get so bad?

Normally, this is where people start ranting about lawyers being evil4. But as far as I can tell, many lawyers are actually quite nice, intelligent people5. If there was a big dial marked “legal obstructionism” on the roof of the supreme court, I think lawyers would agree to let us turn it a little bit back to the left.

The problem is incentives around legitimate tradeoffs. Legitimate tradeoffs between spending more time and effort on the legal side of things and just getting things done come up all the time, and lawyers are always going to choose the “do more lawyering” option when they come up.

The obvious incentive is money - it’s hard to make a man understand something when his salary depends on it and all that - and lawyers, who generally get paid hourly, are pretty incentivised to find something to do to fill up more hours. Like all monetary incentives, sometimes this shows up in unsympathetic ways (“haha, I’ll spend an extra two hours I don’t really need on this divorce case to make this poor abused wife pay me $200 extra”), but more usually it shows up in much more sympathetic ways (“I need to finish X billable hours to not get fired… we’re being paid by a faceless megacorp, why not make extra sure I got it right”). But most of the time it’s neither of these. Most of the time it’s just that you have some kind of legitimate tradeoff - something a reasonable non-lawyer might even agree that you should take the extra time to get right - and you consistently fall on the pro-do-more-work side of a 50/50 split, or even a 40/60. These add up.

There’s also the factor that lawyers consider the costs less: Lawyers hate legal proceedings a lot less than non-lawyers (after all, they can tolerate a job that centers around them); of course they’re not going to be as averse to the cost and pain of extra legal proceedings as they should be.

But probably bigger than this is the status effect. Lawyers like to think of themselves as smart (think how many times you’ve heard of brilliant lawyers or brilliant legal arguments, or how many courtroom dramas there are). They’re cognitive elites, and derive status from making complex arguments. Which means that, when presented with an opportunity to make something more complicated than it has to be, there’s a strong tendency to go “oh hey, a chance to demonstrate my brilliant legal mind” and not “oh no, pointless complexity”. And this gets stronger the more elite you are, which is a problem since the more elite lawyers6 also have more power to set trends and set the terms of the arguments.

This is a similar effect to Google’s enshittification: In practice, what users want from IT products are functionality, resiliency, and usability. But software engineers (especially at places like Google and Facebook, which selectively hire and sell themselves as places for cool smart people to work at) want to think of themselves as smart and creative. So instead of spending massive amounts of time digging through Google maps bugs to make it more usable and crash less, or adding JPEG support for Facebook Messenger, they spend times adding pointless new features or rebuilding functional software in gimmicky new ways7. It’s how you get a promotion8.

So that’s how we went from Google having a reputation for cool usable products that everyone loved back in the early 2010s to their flagship generative AI being so bad it knocked 70 billion dollars off their stock price in a day. And lawyers have the exact same negative incentives, with the added feature that at least software engineers are taught the principles of simple, reusable engineering at some point (even if their incentives are set up against it).

Good rules systems are simple, consistent, and implementable by any idiot in a predictable way. Brilliant legal analysis is, by definition, not predictable by idiots (nobody has ever said “that lawyer made an argument so brilliant any idiot could have made it”), and thus produces bad results. If we want an effective legal system, we need to legislate for idiots, not for brilliant lawyers.

A couple of examples here, since I’ve been talking in abstractions for a while:

Lawyers I’ve talked to tend to hate plea deals and see them as miscarriages of justice. But they’re actually pretty great. They let people skip long, painful trials and avoid their risk and uncertainty. Lawyers hate them because, well, they don’t go through the Full Process (and, in fairness, because prosecutors can use the threat of a long painful trial to extract concessions. But that’s because the alternative is to actually have those long painful trials, which is even worse!)

Take this scene from Better Call Saul as an example

Saul is doing the right thing! He has a bunch of clients who can’t afford the time and money of a full trial, so he sits down with the prosecutor and just skips to the conclusions they both know they’d end up with if they went through the whole trial. This is presented as Saul being sleazy (he’s not doing what a Real Lawyer would), but he’s actually being entirely reasonable and leaving everyone involved better off9.

Fruit of the Poison Tree doctrine, and standards of admissible evidence in general, are dumb and bad. They’re really cool ideas from a game theory perspective - it’s fun to think about avoiding bad incentives and counterfactual paths in an adversarial environment - but in practice they just make trials ridiculously long and messy and cause wrong outcomes to be reached through restricting information. If we’re worried about police abuse of power we should just have rules about firing police officers who abuse their power, not weird evidentiary game theory that only makes sense if you think the point of a trial is to be an elaborate chess game between lawyers trying to show off how smart they are and not a simple process to reach a reasonable decision.

Another good thing lawyers seem to hate is quality of life policing that doesn’t involve lawyers and law enforcement, which is clearly a necessary part of public order that we should have more of. Solving problems without involving lawyers is good for non-lawyers (we get fast simple solutions to problems) and bad for lawyers (they lose power and income), so lawyers push to make this sort of policing hard or impossible.

So how do we improve things?

As always with questions like this, it depends on who “we” is.

If God suddenly put me in charge of the entire legal system with unlimited power to reshape it, I’d want to have the goal of all trials and regulatory approvals take days or weeks instead of years or decades (a couple of weeks is plenty of time to review evidence and reach a decision, even on relatively complicated legal questions10 . I’d also want to have more plea deals and a much freer hand with casual community policing. I’d also at least somewhat reduce reliance on precedent and ability to appeal decisions.

This would, in fairness, involve having more risk tolerance for wrong decisions. A lot of the extra legal bureaucracy we have now ends up being pointless, but at least some of it really does reduce error probability. To compensate, we should have generally shorter and more bearable punishments, and smaller per-incident fines11. It would mean somewhat less stigma around past criminal convictions (to reduce the costs of false positives); to make up for it, there should be increasing penalties for repeat offenders (since the false positive rate decreases exponentially with each conviction). I’d also like to see more plea deals (which would ideally be less dangerously coercive once the cost of undergoing a trial goes from years to days or weeks of commitment)12.

If “we” here is one level removed - now let’s say God just put me in charge of some relevant congressional committee instead of making me king - we should focus on designing simpler systems. Try to think about designing laws and legal systems more like software engineers and less like lawyers13. Put people in charge of writing regulations who really hate regulations and hate going to court, instead of having all our regulatory and planning agencies run by lawyers. Even going for goodhartable metrics like minimizing the number of words or pages in the federal regulations registry would help with that.

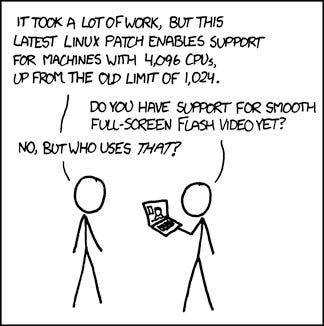

On the personal level - aside from voting for people willing to implement the ideas mentioned above - we should reduce the status of lawyers. The average lawyer is not particularly high-income and doesn’t have an especially exciting job (outside of a right tail spike of biglaw employees).

It should make sense to treat lawyers like we do plumbers - not with disrespect, but just as normal people whose job it is to do standard maintenance on slightly unpleasant infrastructure and get paid a reasonable moderate amount for it14. It shouldn’t be a dream job for cognitive elites. We’d be better off that way on both fronts - blander lawyers would make the legal system better, and those thousands of smart hardworking people could do more good in other jobs where the marginal work hour has a positive instead of negative contribution.

And finally, we should be more willing to disregard legal advice when lawyers tell us to lawyer up and be careful about things. By all means get yourself a good lawyer for your divorce-murder trial, but in general be a bit more willing to do things with less legal CYA than lawyers recommend. They really do have unaligned interests with you there.

And this remains true if you think it was all just pointless legal harassment! Legal harassment cases are even more important to resolve promptly!

An even more egregious example is Bibi Netanyahu’s corruption trial, which at this point has lasted over a decade and approximately three hundred Israeli elections, not to mention the massive civil strife it causes in its wake. Wouldn’t it be nice to live in a world where this gets closed off in a few weeks?

Whenever this comes up people argue that sure, China manages this, but only because they’re terrible and authoritarian in ways we wouldn’t want to live with. But on a per-capita basis they’re not even the best infrastructure builders - Spain, South Korea, and Sweden have all built more than China per capita at less cost per mile. China’s just really big.

I’ve heard some people have even made humorous observations to this effect.

Conflict of interest: Both my brother and my (very nice and wholesome) ex-girlfriend are lawyers.

Which often include judges, legislators, and heads of regulatory agencies.

When I worked at Google, they had four or five different internal SQL variants, none of which was fully compatible with standard SQL. By now they probably have more.

Google explicitly has “innovativeness” as part of their employee evaluation criteria. If you built a great, functional product that everyone loves but didn’t manage to shove some buzzwordy AI thing in there somewhere, you can get denied promotion over that. And now you know why Google had a dozen different chat apps with different weird gimmicks.

I guess rigging the elevator to trick the prosecutor to go along with it is a bit sleazy, but on the object level, he’s right and she’s wrong about this being a better process.

For example, while the CAHSR environmental approval process took over twenty years, the Madrid Metro had a 24 hour approval turnaround time for sudden plan changes when encountering unexpected geology.

In particular, I think this implies abolishing the death penalty; Even if you believe it’s fully appropriate for some horrific crimes, in practice we end up litigating it for decades and would end up having an even higher error margin and more activism about it if we had shorter trials with a higher error rate.

One thing I don’t especially support here is using betting markets or other river-y methods to try to make more accurate legal decisions. The most important thing for the legal system is to be implemented consistently and predictably, even when this is done by mediocre people, which means it has to be done by the village. We can’t trust it to be run by smart competitive river people.

One reason to be optimistic about the future of America is the massive rise in the number of college students majoring in CS and other hard sciences over the last decade. As they rise into positions of authority, we’re likely to see some improvement in competence as more positions are filled by people with some kind of STEM background.

The part of the analogy where a small fraction of them is unexpectedly wealthy also holds up.

As someone who is not a lawyer but works with them, your article is well-written and I can tell you've thought about it a lot, but, it's not even close to accurately describing the internal workings of the legal world. I could probably write a whole article just responding to yours, but a few things:

1. Lawyers LOVE plea deals. And settlements, for non-criminal cases. 98% of federal criminal cases end in plea deals and if my memory's right, it's in the 90s for state criminal cases as well. Lawyers love it when they don't have to go to trial and can clear off their calendar for the day. No one who's actually in the legal field views settling a case as anything sketchy or "less than" than going to trial. If anything, I'd say that more lawyers violate ethical standards by convincing their client to forego their trial and take a plea deal that's not in their best interest.

2. People from outside the legal field view their cases as slogging along at a snail's speed, but for the people in the legal field, they're going at a breakneck pace. You speculate that a couple of weeks is "plenty of time" to review all the evidence in a case and make a decision. That's laughable. You might not even know what evidence there is within a few weeks. You have to meet with your client, find out their story, file an appearance as their attorney, get any pleadings that were already filed in the case, determine what evidence the prosecutor has on them, figure out what points of law and fact can be argued, subpoena places to get records which will take at least two weeks, figure out potential witnesses, find those witnesses, convince them to talk with you, meet with those witnesses and find out what their story would be if they were to testify, prepare questions that you would ask them if you go to trial, subpoena them, try to reach a plea deal with opposing, review their offers with your client, prepare a counter-offer, and then hope to hear back. Decide what evidence you want to use as exhibits. Disclose your witnesses and exhibits to opposing. Look over opposing's disclosures with your client and see if anything makes him change his mind about that initial settlement offer, ....I sure hope you only have one case to work on!

As it is, in federal cases, defendants have a right to a trial with 70 days of being charged. Most of them waive that right. Why? Because they want their attorney to have more time to gather evidence to support their position. If you were to have a trial within a few weeks, the only thing you would get is a lot more appeals as evidence continued to be discovered after the trial date.

3. You seem to be under the impression that lawyers are the ones that are writing the laws and that they write them to be as complicated as possible for their own benefit. Actually, when laypeople write the laws they end up being a lot more convoluted and cause more issues down the road because 1) there will be contradictions, and 2) they don't define terms. Take a law that says, "no one can drive with marijuana in their system". Seems simple, but what does that actually mean? That you can't be under the influence? Or that you can't have any chemical components from marijuana in your system, even though they could be around for weeks after you smoked it? Sloppy writing like that makes the judicial system have to go back and determine what the intent of the law was a lot more than writing seems overly-detailed but is precise.

“It should make sense to treat lawyers like we do plumbers - not with disrespect, but just as normal people whose job it is to do standard maintenance on slightly unpleasant infrastructure and get paid a reasonable moderate amount for it.”

I don’t agree with everything in the post, but I DO think that if we could wave a magic wand and make people think of lawyers (of which I am one) this way that would be a big step toward improving things.