Fantasy Worlds, Time Traveling Cats, and Computability Theory

I wanted to write this into an actual fantasy book, but at this point it's been bouncing around in my head for six years and I've only written two and a half chapters, so might as well.

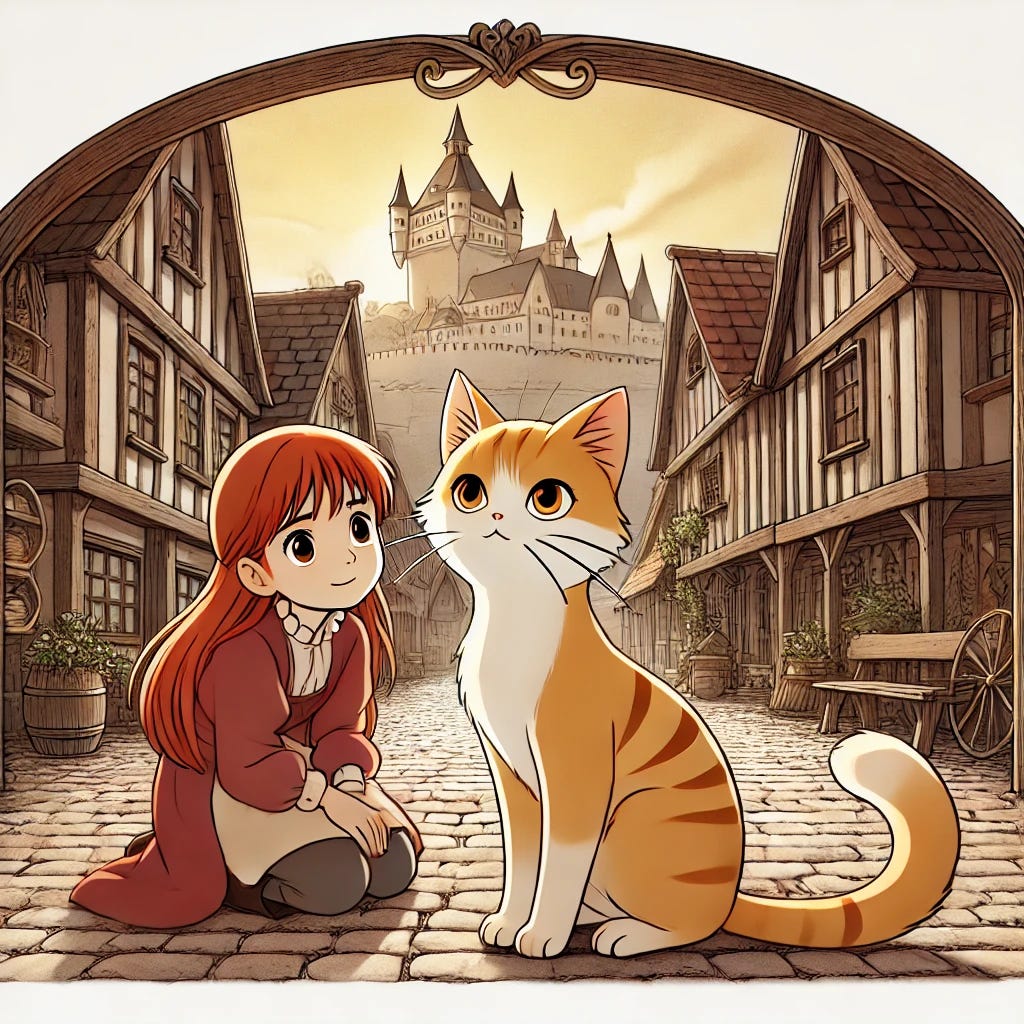

A few years ago, between watching Kiki’s Delivery Service and spending three months backpacking around the western United States, I came up with an idea for a story. It would feature this young girl who grew up to become the scary old witch in the wood, leaving her home to come to the big city on the edge of the waste1 to learn magic. When she gets turned away from the actual magic school, she ends up working as a maid2 and learning magic the hard way from the mysterious man who lives in the attic of the inn, which sometimes exists and sometimes doesn’t. The strange man, unlike the mages at the local academy, actually seems to know the secrets of what magic is really about, so while she learns unconventionally she learns a lot of things no one else seems to know… anyway, there’s a bunch of adventures both around town and out into the waste. Also, she can talk to cats.

Which raises two questions: What is this secret real form of magic that no one seems to know except this one strange man with an inconsistent relationship with reality? And more importantly, why is he the only one who seems to know about it?

The first one is more of an issue of approach: Mainstream mages think of magic constructively, like classical physics: They have a set of rules of things they can do and ways to combine them, like Newton or Maxwell’s equations, and they inductively build up more things they can do with them. They also build up all sorts of external power sources and engines, so they end up with a lot of raw power.

The secret second approach is equivalent to Hamiltonians in physics: There’s some kind of universal field that has to obey certain symmetries or limitations (like being invariant to movements or rotations), and the normal rules (like conservation of energy or momentum) all follow from this3. Understanding magic in this way lets you get it deductively - instead of having to build up the things you can do, you understand what’s impossible and the set of all possible things is much more easily reachable and understandable. It doesn’t give you infinite power, but it lets you understand how to do anything possible within those limits of your power.

…okay, so that answers the first question. But this seems like a pretty natural evolution (and in physics theory, it was a pretty natural evolution; physicists in 1950 didn’t have to be uniquely wise to understand hamiltonians). Why don’t wizards? Because something keeps happening to wizards who understand magic too well.

But before we get into that, let’s talk about time travel for a bit.

There are a lot of challenges involved in making time travel practical: Physics, engineering, making professor McGonagall sad, the possibility of your time machine’s backward-travelling particles colliding into past-you’s forward traveling particles and creating a giant smoking hole where there used to be Scotland, grammar… Those are all reasonably solvable issues though.

The real problem is computability theory. Imagine you’re playing a game of Chess (or Go, or Checkers). You have the magical ability to see into the future, and you’re very competitive and want to win.

So you do. After all, if you saw yourself losing, you’d look at your moves, pick some point at which you made what seems like a losing move, and do something else. Since that creates a contradiction, the only possible consistent path through time is the one where you saw yourself playing perfectly and did. Any other time path would lead to something else, so it can’t happen.

Knowers of computer science will recognize this as a PSPACE complete problem4. It’s computationally intractable5 to solve this with your limited human brain ability, and since the computation has to happen somewhere, it means you don’t get to see the future if seeing the future causes these calculations to happen. There’s a few ways around this:

You can magically give people future sight if you know how. The Mysterious Wizard guy figured it out working in the king’s research lab shortly before he vanished, and used it to create supersoldier knights. But their future sight is very limited (usually to only a few seconds ahead), when the computations required are still small enough to be tractable (they had to be selected to be unusually quick-thinking soldiers for even that). A few seconds into the future is plenty of time for a knight to see and avoid almost any weapon, though, which makes it enough to make them a basically unstoppable army (especially when given a few extra magical weapons and healing powers).

You can see the future better if you’re more ambivalent about it: The more timelines you find acceptable, the less compute heavy it is to pick a future that works for you. The girl’s older brother, who’s one of the captains of the knights, is unusually good at seeing into the future because of this. He has some kind of quiet faith in his religion, which makes him accept more timelines than most as just the way things are, which lets him see further ahead.

Cats are the biologically evolved ultimate version of this: They can see the future perfectly, always, because they’re almost completely aloof and don’t care about almost anything6. You know how cats seem to react to things that aren’t there, or to completely ignore things that are? This is why.

Cats have nine lives because they care enough to narrowly avoid their deaths nine times, because that’s just about the limits of computation a cat can do. After that they’re on their own.You can magically modify yourself to not care about most things. This is what Mysterious Wizard Guy did: In his work on researching how to make future-seeing supersoldiers, he got a glimpse into how magic can be used for real future sight, and even how to step outside of time.

But when he saw this, he also saw the king was sending men to kill him, to destroy the secret of making supersoldiers so it couldn’t be used against him, and he didn’t have much time to explore it. So he did the only thing he had time to, and magically altered his own preferences to care about very little else besides survival. This left enough paths into the future that he could compute one that let him avoid the guards and escape, living at the edges of reality.

It also justifies why he’s an indifferent mentor figure who seems to be fairly unhelpful about warning his protege about getting in dangerous situations. Even if he saw her dying, he probably wouldn’t be able to step in to save her. He modified himself too much, and is only partly of this world anymore.Finally, there’s what all the wizards who understood magic well enough to figure out future sight ended up doing before: You stop existing, mostly. You pick a rule, some vector in which you require the future to happen, and change the world to match it. Then you stop existing in this reality, so that you have no more recursive interactions with the timeline and don’t have computability limits anymore.

There’s some (implied, never explicitly stated) theories that this is actually where all the limitations on magic come from: They’re not fundamental symmetry rules, but they’re just there because some previous ascended wizard put them in as part of his ascension7. And the core rules of the world were probably made by the first wizard who figured out how to step outside of time.

This also, incidentally, gives a strange answer to theodicy: You may ask, if the future was originally set by a mostly-benevolent wizard (or a series of them), why do bad things still happen to good people? Sure you can say something about free will but the results still seem not completely satisfactory.

But this actually makes sense if you consider the limits of morality and free will as having been made by a mostly-decent, fairly wise wizard (with a series of later kludges by subsequent ascensions) and probably some slightly different values than we have. The fantasy world is better than ours - people generally don’t die without closure, and people who really want to live for centuries usually find a way, and there’s no hell (or places that look like hell on earth). Most people live reasonably idyllic lives in the style of the moomins or Kiki’s Delivery Service’s town. But real danger and bad things do still happen, and the world isn’t perfect, because the guy whose job it was to fix it was, in some ways, only human.

The hill the city is on turns out to be the back of the local archmage’s giant pet tortoise, of course.

I promise this is the last part I lifted directly from Kiki’s delivery service.

Except in our case the limits are more about computability than symmetry, but we’ll get to that in a bit.

Technically chess is EXPTIME complete since a match can go on for an exponentially long time, but the time looping part only requires PSPACE. You’d need an exponentially sized memory and exponential patience (in addition to future sight) to play an EXPTIME hard chess game, and you have neither.

Unless P=PSPACE, which is ridiculous even in a fantasy world with witches and turtle cities.

from cats’ perspective, time doesn’t even really have a direction, since they can pretty much see it all at once anyway.

Possibly this even applies to the fundamental laws of computability theory, though I’m not entirely sure that makes sense. But P/NP and Church-Turing sure feel like something a wizard made up rather than a fundamental law of reality.